KERAJAAN MAJA PAHIT

YANG ADA DI INDONESIA

The Majapahit Empire (Javanese: Karaton Mojopahit, Indonesian: Kerajaan Majapahit) was a vast archipelagic empire based on the island of Java (modern-day Indonesia) from 1293 to around 1500. Majapahit reached its peak of glory during the era of Hayam Wuruk, whose reign from 1350 to 1389 was marked by conquest which extended through Southeast Asia. His achievement is also credited to his prime minister, Gajah Mada. According to the Nagarakretagama (Desawarñana) written in 1365, Majapahit was an empire of 98 tributaries, stretching from Sumatra to New Guinea;[4] consisting of present-day Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, southern Thailand, Sulu Archipelago, Philippines, and East Timor, although the true nature of Majapahit sphere of influence is still the subject of studies among historians.[5]

Majapahit was one of the last major empires of the region and is considered to be one of the greatest and most powerful empires in the history of Indonesia and Southeast Asia, one that is sometimes seen as the precedent for Indonesia's modern boundaries.[6](p19)[7] Its influence extended beyond the modern territory of Indonesia and has been the subject of many studies.[8][9]

Etymology

The name Majapahit derives from local Javanese, meaning "bitter maja". German orientalist Berthold Laufer suggested that maja came from the Javanese name of Aegle marmelos, an Indonesian tree.[10] The name originally referred to the area in and around Trowulan, the cradle of Majapahit, which was linked to the establishment of a village in Tarik timberland by Raden Wijaya. It was said that the workers clearing the Tarik timberland encountered some bael trees and consumed its bitter-tasting fruit that subsequently become the village's name.[2] In ancient Java it is common to refer the kingdom with its capital's name. Majapahit (sometimes also spelled Mojopait) is also known by other names: Wilwatikta, although sometimes the natives refer to their kingdom as Bhumi Jawa or Mandala Jawa instead.Historiography

Little physical evidence of Majapahit remains,[11] and some details of the history are rather abstract.[6](p18) Nevertheless, local Javanese people did not forget Majapahit completely, as Mojopait is mentioned vaguely in Babad Tanah Jawi, a Javanese chronicle composed in the 18th century. Majapahit did produce physical evidence: the main ruins dating from the Majapahit period are clustered in the Trowulan area, which was the royal capital of the kingdom. The Trowulan archaeological site was discovered in the 19th century by Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies from 1811 to 1816. He reported the existence of "ruins of temples.... scattered about the country for many miles", and referred to Trowulan as "this pride of Java".[12]By the early 20th century, Dutch colonial historians began to study old Javanese and Balinese literature to explore the past of their colony. Two primary sources were available to them: the Pararaton ('Book of Kings') manuscript was written in the Kawi language c. 1600, and Nagarakertagama (Desawarnaña) was composed in Old Javanese in 1365.[13] Pararaton focuses on Ken Arok, the founder of Singhasari, but includes a number of shorter narrative fragments about the formation of Majapahit. Nagarakertagama is an old Javanese epic poem written during the Majapahit golden age under the reign of Hayam Wuruk, after which some events are covered narratively.[6](p18) The Dutch acquired the manuscript in 1894 during their military expedition against the Cakranegara royal house of Lombok. There are also some inscriptions in Old Javanese and Chinese.

The Javanese sources incorporate some poetic mythological elements, and scholars such as C. C. Berg, an Indonesia-born Dutch naturalist, have considered the entire historical record to be not a record of the past, but a supernatural means by which the future can be determined.[ii][5] Most scholars do not accept this view, as the historical record corresponds with Chinese materials that could not have had similar intention. The list of rulers and details of the state structure show no sign of being invented.[6](p18)

The Chinese historical sources on Majapahit, mainly owed to Zheng He's account — a Ming Dynasty admiral reports during his visit to Majapahit. Zheng He's translator Ma Huan wrote a detailed description of Majapahit and where the king of Java lived.[15] The report was composed and collected in Yingyai Shenglan, which provides a valuable insight on the culture, customs, also various social and economic aspects of Chao-Wa (Java) during Majapahit period.

The Trowulan archaeological area has become the center for the study of Majapahit history. The aerial and satellite imagery has revealed extensive network of canals criss-crossing the Majapahit capital.[16] Recent archaeological findings from April 2011 indicate the Majapahit capital was much larger than previously believed after some artefacts were uncovered.[17]

History

Formation

After defeating the Melayu Kingdom[18] in Sumatra in 1290, Singhasari became the most powerful kingdom in the region. Kublai Khan, the Great Khan of the Mongol Empire and the Emperor of the Mongol Yuan Dynasty, challenged Singhasari by sending emissaries demanding tribute. Kertanegara, the last ruler of Singhasari, refused to pay the tribute, insulted the Mongol envoy and challenged the Khan instead. As the response, in 1293, Kublai Khan sent a massive expedition of 1,000 ships to Java.

King Kertarajasa portrayed as Harihara, amalgamation of Shiva and Vishnu. Originally located at Candi Simping, Blitar, today it is displayed in National Museum.

In 1293, Raden Wijaya founded a stronghold with the capital Majapahit.[20]:200–201 The exact date used as the birth of the Majapahit kingdom is the day of his coronation, the 15th of Kartika month in the year 1215 using the Javanese çaka calendar, which equates to 10 November 1293.[2] During his coronation he was given formal name Kertarajasa Jayawardhana. King Kertarajasa took all four daughters of Kertanegara as his wives, his first wife and prime queen consort Tribhuwaneswari, and her sisters; Prajnaparamita, Narendraduhita, and Gayatri Rajapatni the youngest. He also took a Sumatran Malay Dharmasraya princess named Dara Petak as his wife. The new kingdom faced challenges. Some of Kertarajasa's most trusted men, including Ranggalawe, Sora, and Nambi rebelled against him, though unsuccessfully. It was suspected that the mahapati (equal with prime minister) Halayudha set the conspiracy to overthrow all of the king's opponents, to gain the highest position in the government. However, following the death of the last rebel Kuti, Halayudha was captured and jailed for his tricks, and then sentenced to death.[19] Wijaya himself died in 1309.

According to tradition, Wijaya's son and successor, Jayanegara was notorious for immorality. One of his sinful acts was his desire on taking his own stepsisters as wives. He was entitled Kala Gemet, or "weak villain". Approximately during Jayanegara's reign, the Italian Friar Odoric of Pordenone visited Majapahit court in Java. In 1328, Jayanegara was murdered by his doctor, Tanca. His stepmother, Gayatri Rajapatni, was supposed to replace him, but Rajapatni had retired from the court to become a Bhikkhuni. Rajapatni appointed her daughter, Tribhuwana Wijayatunggadewi, or known in her formal name as Tribhuwannottungadewi Jayawishnuwardhani, as the queen of Majapahit under Rajapatni's auspices. Tribhuwana appointed Gajah Mada as the Prime Minister in 1336. During his inauguration Gajah Mada declared his Sumpah Palapa, revealing his plan to expand Majapahit realm and building an empire.[7]

Golden age

Expansion and decline of Majapahit Empire, started in Trowulan Majapahit

in the 13th century, expanded to much of Indonesian archipelago, until

receded and fell in the early 16th century.

Hayam Wuruk, also known as Rajasanagara, ruled Majapahit in 1350–1389. During this period, Majapahit attained its peak with the help of prime minister, Gajah Mada. Under Gajah Mada's command (1313–1364), Majapahit conquered more territories and become the regional power.[20]:234 According to the book of Nagarakertagama pupuh (canto) XIII and XIV mentioned several states in Sumatra, Malay Peninsula, Borneo, Sulawesi, Nusa Tenggara islands, Maluku, New Guinea, and some parts of Philippines islands as under Majapahit realm of power. This source mentioned of Majapahit expansions has marked the greatest extent of Majapahit empire. This empire also serve as one of the most influential empires in the Indonesian history. It is considered as a commercial trading empire in the civilisation of Asia.

The terracotta figure popularly believed as the portrait of Gajah Mada, collection of Trowulan Museum.

The Nagarakertagama, written in 1365, depicts a sophisticated court with refined taste in art and literature, and a complex system of religious rituals. The poet describes Majapahit as the centre of a huge mandala extending from New Guinea and Maluku to Sumatra and Malay Peninsula. Local traditions in many parts of Indonesia retain accounts in more or less legendary form from 14th-century Majapahit's power. Majapahit's direct administration did not extend beyond east Java and Bali, but challenges to Majapahit's claim to overlordship in outer islands drew forceful responses.[24](p106)

In 1377, a few years after Gajah Mada's death, Majapahit sent a punitive naval attack against a rebellion in Palembang,[6](p19) contributing to the end of the Srivijayan kingdom. Gajah Mada's other renowned general was Adityawarman[citation needed], known for his conquest in Minangkabau.

In 14th-century a Malay Kingdom of Singapura was established, and promptly it attracted Majapahit navy that regard it as Tumasik, their rebellious colony. Singapura was finally sacked by Majapahit in 1398.[25][26][27] The last king, Sri Iskandar Shah fled to the west coast of Malay Peninsula to establish Melaka Sultanate in 1400.

The nature of the Majapahit empire and its extent is subject to debate. It may have had limited or entirely notional influence over some of the tributary states including Sumatra, the Malay Peninsula, Kalimantan and eastern Indonesia over which of authority was claimed in the Nagarakertagama.[28] Geographical and economic constraints suggest that rather than a regular centralised authority, the outer states were most likely to have been connected mainly by trade connections, which was probably a royal monopoly.[6](p19) It also claimed relationships with Champa, Cambodia, Siam, southern Burma, and Vietnam, and even sent missions to China.[6](p19)

Although the Majapahit rulers extended their power over other islands and destroyed neighbouring kingdoms, their focus seems to have been on controlling and gaining a larger share of the commercial trade that passed through the archipelago. About the time Majapahit was founded, Muslim traders and proselytisers began entering the area.

Decline

Following Hayam Wuruk's death in 1389, Majapahit power entered a period of decline with conflict over succession.[20]:241 Hayam Wuruk was succeeded by the crown princess Kusumawardhani, who married a relative, Prince Wikramawardhana. Hayam Wuruk also had a son from his previous marriage, crown prince Wirabhumi, who also claimed the throne. A civil war, called Paregreg, is thought to have occurred from 1405 to 1406,[6](p18) of which Wikramawardhana was victorious and Wirabhumi was caught and decapitated. The civil war weakened Majapahit's grip on its outer vassals and colonies.

The mortuary deified portrait statue of Queen Suhita (reign 1429-1447), discovered at Jebuk, Kalangbret, Tulungagung, East Java, National Museum of Indonesia.

Wikramawardhana ruled until 1426 and was succeeded by his daughter Suhita,[20]:242 who ruled from 1426 to 1447. She was the second child of Wikramawardhana by a concubine who was the daughter of Wirabhumi. In 1447, Suhita died and was succeeded by Kertawijaya, her brother.[20]:242 He ruled until 1451. After Kertawijaya died, Bhre Pamotan became a king with formal name Rajasawardhana and ruled at Kahuripan. He died in 1453. A three-year kingless period was possibly the result of a succession crisis. Girisawardhana, son of Kertawijaya, came to power in 1456. He died in 1466 and was succeeded by Singhawikramawardhana. In 1468 Prince Kertabhumi rebelled against Singhawikramawardhana, promoting himself king of Majapahit. Singhawikramawardhana moved the kingdom’s capital further inland to Daha (the former capital of Kediri kingdom), effectively splitting Majapahit, under Bhre Kertabumi in Trowulan and Singhawikramawardhana in Daha. Singhawikramawardhana continued his rule until he was succeeded by his son Ranawijaya in 1474.

In the western part of the crumbling empire, Majapahit found itself unable to control the rising power of the Sultanate of Malacca that in the mid-15th century began to gain effective control of Malacca Strait and expand its influence to Sumatra. Several other former Majapahit vassals and colonies began to release themselves from Majapahit domination and suzerainty. But Kertabhumi managed to reverse this event, under his rule he allied Majapahit with Muslim merchants, giving them trading rights on the north coast of Java, with Demak as its centre and in return he asked for their loyalty to Majapahit. This policy boosted the Majapahit treasury and power but weakened Hindu-Buddhism as its main religion because Islam spread faster. Hindu-Buddhist followers' grievances later paved the way for Ranawijaya to defeat Kertabumi.

The model of a Majapahit ship display in Muzium Negara, Kuala Lumpur.

In 1498, there was a turning point when Girindrawardhana was deposed by his vice regent, Udara. After this coup, the war between Demak and Daha receded, with some sources saying Raden Patah left Majapahit alone as his father had done before, while others said Udara agreed to become a vassal of Demak, even marrying Raden Patah's youngest daughter. But this delicate balance ended when Udara asked Portugal for help in Malacca and forced Demak to attack Malacca and Daha under Adipati Yunus to end this co-operation.[iv] A large number of courtiers, artisans, priests, and members of the royalty moved east to the island of Bali. The refugees probably fled to avoid Demak retribution for their support for Ranawijaya against Kertabhumi.

With the fall of Daha, crushed by Demak in 1517,[6](pp36–37) the Muslim emerging forces finally defeated the remnants of the Majapahit kingdom in the early 16th century.[34] Demak came under the leadership of Raden (later crowned as Sultan) Patah (Arabic name: Fatah), who was acknowledged as the legitimate successor of Majapahit. According to Babad Tanah Jawi and Demak tradition, the source of Patah's legitimacy was because their first sultan, Raden Patah, was the son of Majapahit king Brawijaya V with a Chinese concubine. Another argument supports Demak as the successor of Majapahit; the rising Demak sultanate was easily accepted as the nominal regional ruler, as Demak was the former Majapahit vassal and located near the former Majapahit realm in Eastern Java.

Demak established itself as the regional power and the first Islamic sultanate in Java. After the fall of Majapahit, the Hindu kingdoms in Java only remained in Blambangan on the eastern edge and Pajajaran in the western part. Gradually Hindu communities began to retreat to the mountain ranges in East Java and also to the neighbouring island of Bali. A small enclave of Hindu communities still remain in the Tengger mountain range.

Culture, art and architecture

The main event of the administrative calendar took place on the first day of the month of Caitra (March–April) when representatives from all territories paying tax or tribute to Majapahit came to the capital to pay court. Majapahit's territories were roughly divided into three types: the palace and its vicinity; the areas of east Java and Bali which were directly administered by officials appointed by the king; and the outer dependencies which enjoyed substantial internal autonomy.[24](p107)Culture

The first European record about Majapahit came from the travel log of the Italian Mattiussi, a Franciscan monk. In his book: "Travels of Friar Odoric of Pordenone", he visited several places in today's Indonesia: Sumatra, Java, and Banjarmasin in Borneo, between 1318–1330. He was sent by the Pope to launch a mission into the Asian interiors. In 1318 he departed from Padua, crossed the Black Sea into Persia, all the way across Calcutta, Madras, and Sri Lanka. He then headed to Nicobar island all the way to Sumatra, before visiting Java and Banjarmasin. He returned to Italy by land through Vietnam, China, all the way through the silkroad to Europe in 1330.

In his book he mentioned that he visited Java without explaining the exact place he had visited. He said that king of Java ruled over seven other kings (vassals). He also mentioned that in this island was found a lot of clove, cubeb, nutmeg and many other spices. He mentioned that the King of Java had an impressive, grand, and luxurious palace. The stairs and palace interior were coated with gold and silver, and even the roofs were gilded. He also recorded that the kings of the Mongol had repeatedly tried to attack Java, but always ended up in failure and managed to be sent back to the mainland. The Javanese kingdom mentioned in this record is Majapahit, and the time of his visit is between 1318–1330 during the reign of Jayanegara.

In Yingyai Shenglan — a record about Zheng He's expedition (1405-1433) — Ma Huan describes the culture, customs, various social and economic aspects of Chao-Wa (Java) during Majapahit period. Ma Huan visited Java during Zheng He's 4th expedition in the 1413, during the reign of Majapahit king Wikramawardhana. He describes his travel to Majapahit capital, first he arrived to the port of Tu-pan (Tuban) where he saw large numbers of Chinese settlers migrated from Guangdong and Chou Chang. Then he sailed east to thriving new trading town of Ko-erh-hsi (Gresik), Su-pa-erh-ya (Surabaya), and then sailing inland into the river by smaller boat to southwest until reached the river port of Chang-ku (Changgu). Continued travel by land to southwest he arrived in Man-che-po-I (Majapahit), where the king stay. There are about 200 or 300 foreign families resides in this place, with seven or eight leaders to serve the king. The climate is constantly hot, like summer.[15] He describes the king’s costumes; wearing a crown of gold leaves and flowers or sometimes without any headgear; bare-chested without wearing a robe, the bottom parts wears two sash of embroidered silk. Additional silk rope is looped around the waist as a belt, and the belt is inserted with one or two short blades, called pu-la-t'ou (belati or more precisely kris dagger), walking barefoot. When travelling outside, the king riding an elephant or an ox-drawn carriage.[15]

The graceful Bidadari Majapahit, golden celestial apsara in Majapahit style perfectly describes Majapahit as "the golden age" of the archipelago.

Majapahit people, men and women, favoured their head.[vi] If someone was touched on his head, or if there is a misunderstanding or argument when drunk, they will instantly draw their knives and stab each other. When the one being stabbed was wounded and dead, the murderer will flee and hide for three days, then he will not lose his life. But if he was caught during the fight, he will instantly stabbed to death (execution by stabbing). The country of Majapahit knows no caning for major or minor punishment. They tied the guilty men on his hands in the back with rattan rope and paraded them, and then stabbed the offender in the back where there is a floating rib which resulted in instant death.[15] Judicial executions of this kind were frequent.

Population of the country did not have a bed or chair to sit, and to eat they do not use a spoon or chopsticks. Men and women enjoy chewing betel nut mixed with, betel leaves, and white chalk made from ground mussels shells. They eat rice for meal, first they took a scoop of water and soak betel in their mouth, then wash their hands and sit down to make a circle; getting a plate of rice soaked in butter (probably coconut milk) and gravy, and eat using hands to lift the rice and put it in their mouth. When receiving guests, they will offer the guests, not the tea, but with betel nut.[15]

The population consisted of Muslim merchants from the west (Arab and Muslim Indians, but mostly those from Muslim states in Sumatra), Chinese (claimed to be descendants of Tang dynasty), and unrefined locals. The king held annual jousting tournaments.[15](p45) About the marriage rituals; the groom pays a visit to the house of the bride's family, the marriage union is consummated. Three days later, the groom escorts his bride back to his home, where the man’s family beat drums and brass gongs, blowing pipes made from coconut shells (senterewe), beating a drum made from bamboo tubes (probably a kind of bamboo gamelan or kolintang), and light fireworks. Escorted in front, behind, and around by men holding short blades and shields. While the bride is a matted-hair woman, with uncovered body and barefooted. She wraps herself in embroidered silk, wears a necklace around her neck adorned with gold beads, and bracelets on her wrist with ornaments of gold, silver and other precious ornaments. Family, friends and neighbours decorate a decorative boat with betel leaf, areca nut, reeds and flowers were sewn, and arrange a party to welcome the couple on such a festive occasion. When the groom arrives home, the gong and drum are sounded, they will drink wine (possibly arack or tuak) and play music. After a few days the festivities end.[15]

About the burial rituals, the dead body was left on beach or empty land to be devoured by dogs (for lower-class), cremated, or committed into the waters (Javanese:larung). The upper-class performed suttee, a ritual suicide by widowed wives, concubines or female servants, through self immolation by throwing themselves into flaming cremation fire.[15]

For the writing, they had known the alphabet using So-li (Chola - Coromandel/Southern India) letters. There is no paper or pen, they use Chiao-chang (kajang) or palm leaf (lontar), written by scraping it with a sharp knife. They also have a developed language system and grammar. The way the people talk in this country is very beautiful and soft.[15]

In this record, Ma Huan also describes a musical troupes travelling during full moon nights. Numbers of people holding shoulders creating an unbroken line while singing and chanting in unison, while the families whose houses being visited would give them copper coins or gifts. He also describes a class of artisans that draws various images on paper and give a theatrical performance. The narrator tells the story of legends, tales and romance drawn upon a screen of rolled paper.[15] This kind of performance is identified as wayang bébér, an art of story-telling that has survived for many centuries in Java.

Art

Further information: Majapahit Terracotta

Bas reliefs of Tegowangi temple, dated from Majapahit period, demonstrate the East Javanese style.

Pair of door guardians from a temple, Eastern Java, 14th century (Museum of Asian Art, San Francisco)

Architecture

Further information: Candi of Indonesia

Jabung temple near Paiton, Probolinggo, East Java, dated from Majapahit period.

The houses of commoners had thatched roofs (nipa palm leaves). Every family has a storage shed made of bricks, about 3 or 4 Ch'ih (48.9 inches or 124 centimetres) above the ground, where they kept the family property, and they lived on top of this building, to sit and sleep.

The Majapahit temple architecture follows the east Javanese styles, in contrast of earlier central Javanese style. This east Javanese temple style is also dated back from Kediri period c. 11th century. The shapes of Majapahit temples are tends to be slender and tall, with roof constructed from multiple parts of stepped sections formed a combined roof structure curved upward smoothly creating the perspective illussion that the temple is perceived taller than its actual height. The pinnacle of the temples are usually cube (mostly Hindu temples), sometimes dagoba cylindrical structures (Buddhist temples). Although some of temples dated from Majapahit period used andesite or sandstone, the red bricks is also a popular construction material.

Although brick had been used in the candi of Indonesia's classical age, it was Majapahit architects of the 14th and 15th centuries who mastered it.[36] Making use of a vine sap and palm sugar mortar, their temples had a strong geometric quality. The example of Majapahit temples are Brahu temple in Trowulan, Pari in Sidoarjo, Jabung in Probolinggo, and Surawana temple near Kediri. Some of the temples are dated from earlier period but renovated and expanded during Majapahit era, such as Penataran, the largest temple in East Java dated back to Kediri era. This temple was identified in Nagarakretagama as Palah temple and reported being visited by King Hayam Wuruk during his royal tour across East Java.

The 16.5 metres tall Bajang Ratu gate, at Trowulan, echoed the grandeur of Majapahit.

In later period near the fall of Majapahit, the art and architecture of Majapahit witnessed the revival of indigenous native Austronesian megalithic architectural elements, such as Sukuh and Cetho temples on western slopes of Mount Lawu. Unlike previous Majapahit temples that demonstrate typical Hindu architecture of high-rise towering structure, the shape of these temples are step pyramid, quite similar to Mesoamerican pyramids. The stepped pyramid structure called Punden Berundak (stepped mounds) is a common megalithic structure during Indonesian prehistoric era before the adoption of Hindu-Buddhist culture.

Economy

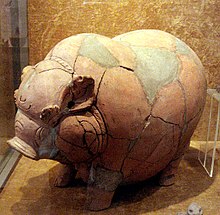

Majapahit Terracotta Piggy Bank, 14th–15th century Trowulan, East Java. (Collection of National Museum of Indonesia, Jakarta)

For the fruits, there are all kinds of bananas, coconut, sugarcane, pomegranate, lotus, mang-chi-shi (mangosteen), watermelon and lang Ch'a (langsat or lanzones). Mang-chi-shi – is something like a pomegranate, peel it like an orange, it has four lumps of white flesh, sweet and sour taste and very delicious. Lang-ch’a is a fruit similar to Loquat, but larger, contained three blocky white flesh with sweet and sour taste. Sugarcane has white stems, large and coarse, with roots reaching 3 chang (30 feet 7 inches). In addition, all types of squash and vegetables are there, just a shortage of peach, plum and leek.[15]

Taxes and fines were paid in cash. Javanese economy had been partly monetised since the late 8th century, using gold and silver coins. Previously, the 9th century Wonoboyo hoard discovered in Central Java shows that ancient Javan gold coins were seed-shaped, similar to corn, while the silver coins were similar to buttons. In about the year 1300, in the reign of Majapahit's first king, an important change took place: the indigenous coinage was completely replaced by imported Chinese copper cash. About 10,388 ancient Chinese coins weighing about 40 kg were even unearthed from the backyard of a local commoner in Sidoarjo in November 2008. Indonesian Ancient Relics Conservation Bureau (BP3) of East Java verified that those coins dated as early as Majapahit era.[37] The reason for using foreign currency is not given in any source, but most scholars assume it was due to the increasing complexity of Javanese economy and a desire for a currency system that used much smaller denominations suitable for use in everyday market transactions. This was a role for which gold and silver are not well suited.[24](p107) These kepeng Chinese coins were thin rounded copper coins with a square hole in the centre of it. The hole was meant to tie together the money in a string of coins. These small changes—the imported Chinese copper coins—enabled Majapahit further invention, a method of savings by using a slitted earthenware coin containers. These are commonly found in Majapahit ruins, the slit is the small opening to put the coins in. The most popular shape is boar-shaped celengan (piggy bank).

The statue of Parvati as mortuary deified portrayal of Tribhuwanottunggadewi, queen of Majapahit, mother of Hayam Wuruk.

The great prosperity of Majapahit was probably due to two factors. Firstly, the northeast lowlands of Java were suitable for rice cultivation, and during Majapahit's prime numerous irrigation projects were undertaken, some with government assistance. Secondly, Majapahit's ports on the north coast were probably significant stations along the route to obtain the spices of Maluku, and as the spices passed through Java they would have provided an important source of income for Majapahit.[24](p107)

The Nagarakertagama states that the fame of the ruler of Wilwatikta (a synonym for Majapahit) attracted foreign merchants from far and wide, including Indians, Khmers, Siamese, and Chinese among others. While in later period, Yingyai Shenglan mentioned that large numbers of Chinese traders and Muslim merchants from west (from Arab and India, but mostly from Muslim states in Sumatra and Malay peninsula) are settling in Majapahit port cities, such as Tuban, Gresik and Hujung Galuh (Surabaya). A special tax was levied against some foreigners, possibly those who had taken up semi-permanent residence in Java and conducted some type of enterprise other than foreign trade. The Majapahit Empire had trading links with Chinese Ming dynasty, Annam and Champa in today Vietnam, Cambodia, Siamese Ayutthayan, Burmese Martaban and the south Indian Vijayanagara Empire.